Three parts down, on to the fourth. This time, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on atheism and agnosticism tries to make an argument for agnosticism. Is it going to be any more impressive than the last couple? I wouldn’t be holding my breath. So far, this has all been “we like this definition” and it’s never been about what the words actually mean, because they aren’t actually handling language the way it at it realistically functions.

Three parts down, on to the fourth. This time, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on atheism and agnosticism tries to make an argument for agnosticism. Is it going to be any more impressive than the last couple? I wouldn’t be holding my breath. So far, this has all been “we like this definition” and it’s never been about what the words actually mean, because they aren’t actually handling language the way it at it realistically functions.

However, we’ll see where this goes and evaluate it as it comes. See you on the other side.

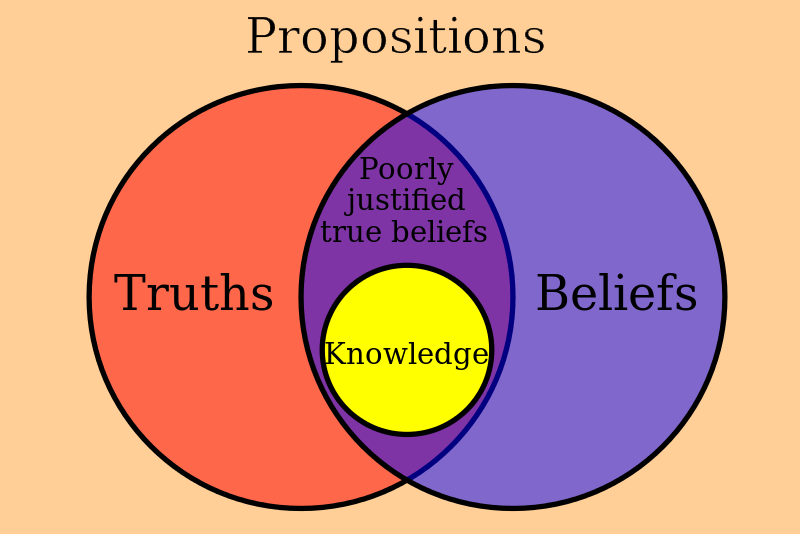

“According to one relatively modest form of agnosticism, neither versatile theism nor its denial, global atheism, is known to be true.” And there they go again. Nobody is claiming that atheism is “true”. It is a negation of theism. It’s theists saying “there is a god” and atheists saying “we don’t believe you!” This might be difficult for philosophers to handle, but too bad. That sounds like a “you” problem. Just because philosophy works best with positive claims, that doesn’t mean they can magically turn everything into a positive claim. My atheism isn’t a positive claim. Deal with it.

Thereafter he proposes a syllogism by Robin Le Poidevin and we’ll evaluate it point by point.

- (1)There is no firm basis upon which to judge that theism or atheism is intrinsically more probable than the other.

Wrong. We can look at what is more likely to be true. We can’t evaluate what is absolutely true but we can look at the evidence that exists and the evidence that we would expect there to be if theism was a rational position to hold and we can come to the conclusion that the evidence for theism is simply unjustified. It’s the same thing we do with any other claim. We can’t prove that Bigfoot isn’t real but we can certainly look at the evidence that we’d expect to find if there really were big hairy creatures in the woods and, based on the complete lack of that evidence, conclude, at least provisionally, that there’s no good reason to believe it.

- (2)There is no firm basis upon which to judge that the total evidence favors theism or atheism over the other.

Except that’s wrong too. While lack of evidence isn’t evidence of lack of existence, it’s certainly a good reason to reject the claims made by the religious, provisionally at least, until they have something coherent to present. This whole false dichotomy thing is nonsense.

It follows from (1) and (2) that

- (3)There is no firm basis upon which to judge that theism or atheism is more probable than the other.

Again, wrong. That is only so if atheism were defined as a positive assertion, which it isn’t. This is really debating a straw man.

It follows from (3) that

- (4)Agnosticism is true: neither theism nor atheism is known to be true.

Except that’s wrong too. Four up, four down. Agnosticism doesn’t even address atheism or theism. It is the answer to an entirely separate question. They are trying desperately to push this on things that virtually no one outside of philosophers and the religious ever say. They’ve entirely neglected to run this past any atheists. That’s kind of a problem, isn’t it?

“Le Poidevin takes “theism” in its broadest sense to refer to the proposition that there exists a being that is the ultimate and intentional cause of the universe’s existence and the ultimate source of love and moral knowledge (2010: 52).” Yet that’s not true either! There are plenty of theists out there whose gods aren’t the ultimate anything, they didn’t create the universe and they don’t have any kind of moral authority. Have these people never considered the Greek, Roman or Egyptian pantheons? It certainly seems not!

“Le Poidevin takes “theism” in its broadest sense to refer to the proposition that there exists a being that is the ultimate and intentional cause of the universe’s existence and the ultimate source of love and moral knowledge (2010: 52).” Yet that’s not true either! There are plenty of theists out there whose gods aren’t the ultimate anything, they didn’t create the universe and they don’t have any kind of moral authority. Have these people never considered the Greek, Roman or Egyptian pantheons? It certainly seems not!

“By the “intrinsic probability” of a proposition, he means, roughly, the probability that a proposition has “before the evidence starts to come in” (2010: 49).” Yet no proposition is even worth considering absent the evidence. This really strikes me as philosophers trying desperately to hide within their ivory towers, confident that their views can provide a complete view of anything, even when that’s demonstrably untrue. It’s probably why a lot of philosophers just run away whenever anyone asks them to produce evidence. “Oh shit, evidence! I’ve gotta go!” This is a problem when you just assume that you’ve got all of the answers when, demonstrably, you just don’t.

Then it gets into how they defend the premises, which I’m going to skip over because it’s not actually defending anything real. This is just a straw man because the terms don’t actually mean what they desperately want them to mean and thus, it’s a complete waste of time to slog through the defense of something that isn’t even reasonable in the first place.

Therefore, let’s find something better. “Of course, even if the two premises of Le Poidevin’s argument are true, it doesn’t follow that the argument is a good one.” That’s obvious. Not only are the two premises false, the whole argument is bad from the start. It’s an argument looking for absolutes where absolutes simply don’t exist. It’s a methodology to evaluate claims made by the religious and determine if those claims stand up to critical scrutiny. It’s not a hard and fast position.

Therefore, let’s find something better. “Of course, even if the two premises of Le Poidevin’s argument are true, it doesn’t follow that the argument is a good one.” That’s obvious. Not only are the two premises false, the whole argument is bad from the start. It’s an argument looking for absolutes where absolutes simply don’t exist. It’s a methodology to evaluate claims made by the religious and determine if those claims stand up to critical scrutiny. It’s not a hard and fast position.

“Concerning the first inference, suppose, for example, that even though there is no firm basis upon which to judge which of theism and atheism is intrinsically more probable (that is, Le Poidevin’s first premise is true), there is firm basis upon which to judge that theism is not many times more probable intrinsically than some specific version of atheism, say, reductive physicalism.” I’m not going to get into how this is completely wrong again, but it is certainly more probable that nature, the only thing that we can actually demonstrate is real, is much more likely than the supernatural, which no one can show exists, nor even define in any coherent way. It’s like claiming “flerglenurgle” is real. Great, first tell us what that is and then tell us how you know anything about it! I think a lot of philosophers are looking for absolutes in a world where absolutes don’t really exist. We can only go by the evidence that we have at hand at the present time. I think that drives a lot of them crazy.

“And suppose that, even though there is no firm basis upon which to judge which of theism and atheism is favored by the total evidence (that is, Le Poidevin’s second premise is true), there is firm basis upon which to judge that the total evidence very strongly favors reductive physicalism over theism (in the sense that it is antecedently very many times more probable given reductive physicalism than it is given theism). ” That much is absolutely true and the reason a lot of people, myself included, are atheists. The evidence just doesn’t line up on the religious side. Given that though, why is this such a difficult proposition for the philosophers to grasp? I think they are looking for things that don’t exist because it is more emotionally satisfying than just admitting that we live in a universe that isn’t certain.

“So it may be that Le Poidevin’s premises, if adequately supported, establish that theistic gnosticism is false (that is, that either agnosticism or atheistic gnosticism is true) even if they don’t establish that agnosticism is true.” Almost. They are still trying to present agnosticism as a separate position when, it’s just not. They don’t seem to have a problem matching gnosticism up with theism or atheism but they can’t do it with agnosticism. Why not? Where is the problem understanding that, while atheism is simply the lack of the quality “theism”, agnosticism is simply the lack of the quality “gnosticism”? This seems to be a serious problem for a lot of philosophers. I wish someone could explain why.

“So it may be that Le Poidevin’s premises, if adequately supported, establish that theistic gnosticism is false (that is, that either agnosticism or atheistic gnosticism is true) even if they don’t establish that agnosticism is true.” Almost. They are still trying to present agnosticism as a separate position when, it’s just not. They don’t seem to have a problem matching gnosticism up with theism or atheism but they can’t do it with agnosticism. Why not? Where is the problem understanding that, while atheism is simply the lack of the quality “theism”, agnosticism is simply the lack of the quality “gnosticism”? This seems to be a serious problem for a lot of philosophers. I wish someone could explain why.